\

\ (Additional content at flickr Photostream and YouTube Channel)

If you have botany questions or comments please email BobK . Thanks!

Two floating-leaved aquatic plants,

and a sea monster (which turned out to be a carp).

July 8 and 10, 2008

Marion and Wyandot Counties, OH

and a sea monster (which turned out to be a carp).

July 8 and 10, 2008

Marion and Wyandot Counties, OH

Some aquatic plants are rooted in the mud

below the water, have flexuous stems that reach up to the surface, and

bear leaves that float like little carpets. Two wholly unrelated

floating-leaved plants that have a markedly similar overall aspect

are

water smartweed (Polygonum coccinium, family Polygonaceae) and

pondweed (Potamogeton natans, family Najadaceae).

The smartweed is growing in Bee Run Ditch, a tributary to the Olentangy (Whetstone) River on Nesbit Rd., Caledonia, Marion County, OH.

Water smartweed, July 8, 2008, Bee Run Ditch, Caledonia, Marion County, Ohio.

Water smartweed, July 8, 2008, Caledonia, Marion County, Ohio.

Water smartweed flowers, July 8, 2008, Caledonia, Ohio.

Floating pondweed flowering spikes, July 10, 2008, Killdeer Plains Wildlife Area, Wyandot County, Ohio.

Floating pondweed flowering spike, Killdeer Plains Wildlife Area, July 10, 2008.

The smartweed is growing in Bee Run Ditch, a tributary to the Olentangy (Whetstone) River on Nesbit Rd., Caledonia, Marion County, OH.

Water smartweed, July 8, 2008, Bee Run Ditch, Caledonia, Marion County, Ohio.

Smartweeds (genus Polygonum)

aren't

particularly intelligent. Instead, the name refers to the sharply

peppery "smarting" taste of some species (not this one). Several

smartweed species produce abundant small seed-like fruits (achenes)

that are valuable for wildlife. Other smartweeds are weedy.

Water smartweed, July 8, 2008, Caledonia, Marion County, Ohio.

I don't know whether water smartweed is

particularly adapted for fly pollination, but there are several flies,

and no other types of insects, on the flowers today.

Water smartweed flowers, July 8, 2008, Caledonia, Ohio.

About 20 miles northwest from the

water smartweed, in a large impoundment at the Killdeer Plains Wildlife

Area, Wyandot County, a more drab but probably more valuable wildlife

food plant is amazingly abundant. It's floating pondweed, Potamgeton

natans (family Najadaceae).

Large impoundment at Killdeer Plains Wildlife Area, Wyandot County, Ohio,

where floating pondweed is remarkably abundant, July 10, 2008.

Large impoundment at Killdeer Plains Wildlife Area, Wyandot County, Ohio,

where floating pondweed is remarkably abundant, July 10, 2008.

Floating pondweed flowering spikes, July 10, 2008, Killdeer Plains Wildlife Area, Wyandot County, Ohio.

Pondweed flowers are presented on an

upright spike, similar to those of the smartweed. Again, there are

insects --stoneflies this time -- associated with the flowers that

may

or may not be important pollinators.

Floating pondweed flowering spike, Killdeer Plains Wildlife Area, July 10, 2008.

After pollination and ripening of the

seed-like fruits (achenes), pondweed spikes lay down, immersing

the

fruits in the water to effect hydrochory (water dispersal).

Scattered here and there in the

impoundment are large-ish (estimated 1-2 feet) creatures noisily

chomping cow-like on the pondweed. They are smooth and dark,

apparently (but impossibly) lacking either fur or fins. The

amorphous head

region seems to project well past the eyes. What are these animals?

Mini-manatees? Space creatures?

Unidentfied aquatic grazing herbivore, July 10, 2008, Killdeer Plains Wildliife Area, Wyandot County, Ohio.

Unidentfied aquatic grazing herbivore, July 10, 2008, Killdeer Plains Wildliife Area, Wyandot County, Ohio.

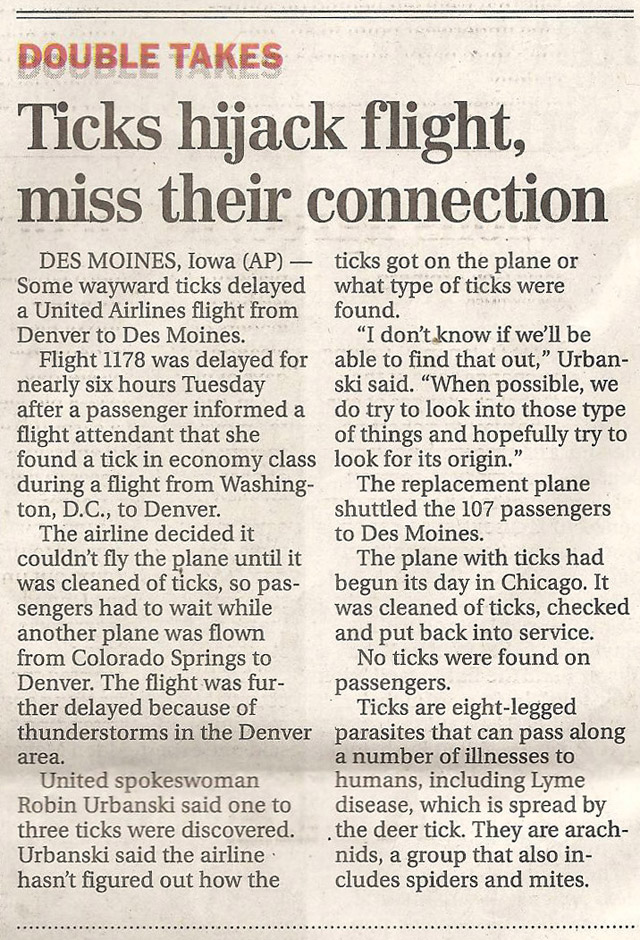

Today's paper tells us that the smart

sensible people who are running our transportion system evacuated a

plane because there was a tick on it. And they have no idea how a tick

could have gotten onto an airplane.

Below are some ticks found on or near a

botanical enthusiast living in Columbus, Ohio, just a few hours after

spending some time outdoors on Planet Earth the same day that

article appeared. Should he (and

all hunters, fishers, hikers, etc.) be placed on the "no-fly list"?

Ticks...I have no idea where they came from!

Sullivant's milkweed (Asclepias

sullivantii,

family Asclepiadaceae), is an uncommon prairie species. Even though we

are at the eastern edge of its range, the species was discovered in

Ohio. The discovery was made by William Starling Sullivant, a

prominent 19th century American botanist who was mainly into mosses.

His was an important family locally. William's father

was Lucas Sullivant, a land

surveyor and developer who, in 1797, founded Franklinton, the

first big settlement in the area (later annexed by Columbus).

At the Greenlawn Cemetery in Columbus, here is the Sullivant family burial site, showing the graves of (left to right): father Lucas, William's beloved wife Eliza who was herself an accomplished botanist (she worked alongside her husband and made illustrations for his moss books), and William.

Sullivant family burial site at Greenlawn Cemetery, October, 2004

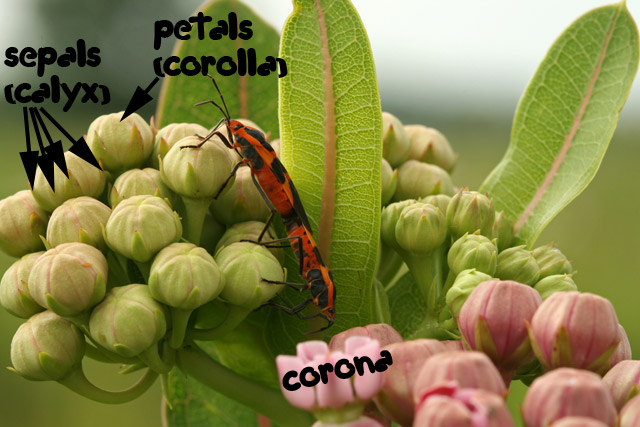

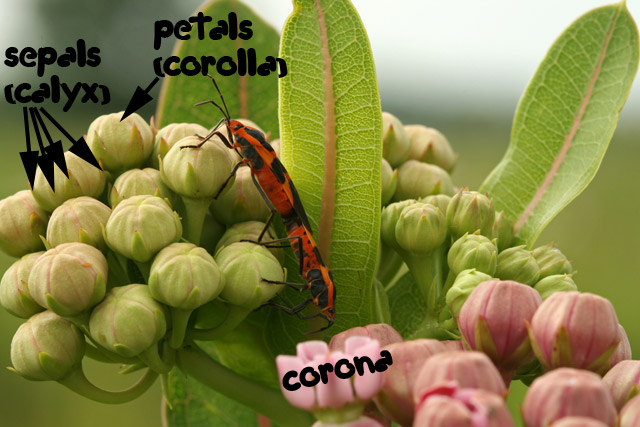

Milkweed flowers are highly modified. The buds are enveloped by the petals. The major pollinator-attractive (and also the reward-providing) portion of the flower is an elaborate set of tubular upward extensions of the petals collectively termed the "corona."

Sullivant's milkweed umbels in the bud stage (except for one flower).

Killdeer Plains Wildlife Area, July 5, 2008.

At the Greenlawn Cemetery in Columbus, here is the Sullivant family burial site, showing the graves of (left to right): father Lucas, William's beloved wife Eliza who was herself an accomplished botanist (she worked alongside her husband and made illustrations for his moss books), and William.

Sullivant family burial site at Greenlawn Cemetery, October, 2004

Eliza's monument is particularly

interesting from a botanical perspective. The plant she is festooned by

is another Sullivant discovery, one with a doubly commemorative name:

the woodland herb Sullivantia sullivantii (family

Saxifragaceae).

Left: Eliza Sullivant monument at Greenlawn Cemetery. Right: illustration of Sullivantia sulivantii from Flora of West Virginia (Strausbaugh and Core).

The milkweeds that bear Sullivant's name are flowering profusely. The Killdeer Plains population is Ohio's largest.

Sullivant's milkweed, Killdeer Plains Wildlife Area, July 4, 2008

Left: Eliza Sullivant monument at Greenlawn Cemetery. Right: illustration of Sullivantia sulivantii from Flora of West Virginia (Strausbaugh and Core).

The milkweeds that bear Sullivant's name are flowering profusely. The Killdeer Plains population is Ohio's largest.

Sullivant's milkweed, Killdeer Plains Wildlife Area, July 4, 2008

Milkweeds are avidly visited by a variety

of insects. According to the literature, both butterflies and bees are

common as pollinators, but at Killdeer it's honeybees, and to a

lesser extent bumblebees, that seem to do it all. Butterflies are

scarce and fleeting at Killdeer. (Butterflies just flutter by.)

Sullivant's milkweed visited by honeybee, Killdeer Plains Wildlife Area, July 5, 2008.

Sullivant's milkweed visited by honeybee, Killdeer Plains Wildlife Area, July 5, 2008.

Milkweed flowers are highly modified. The buds are enveloped by the petals. The major pollinator-attractive (and also the reward-providing) portion of the flower is an elaborate set of tubular upward extensions of the petals collectively termed the "corona."

Sullivant's milkweed umbels in the bud stage (except for one flower).

Killdeer Plains Wildlife Area, July 5, 2008.

While

blooming, milkweed petals are spread sharply downwards,

concealing the sepals. The individual units of the corona are the

"hoods," cup-like structures that serve as nectar basins,

providing a

tremendous food resource for a variety of insects that come and avidly

drink from them.

Fly visiting Sullivant's milkweed, Killdeer Plains Wildlife Area. July 5, 2008.

Bumblebee drinking milkweed nectar, Killdeer Plains Wildlife Area, July 5, 2008.

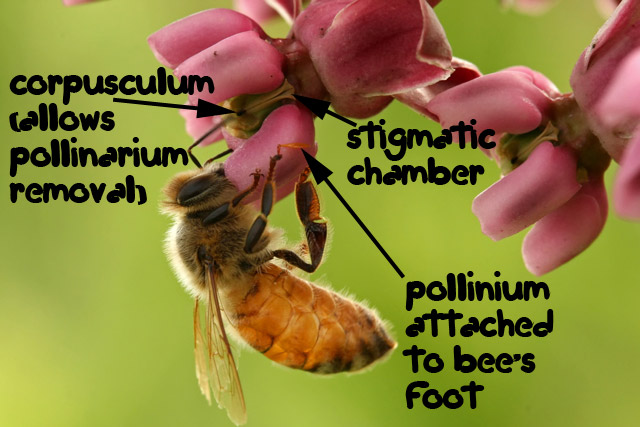

Milkweed

flower structure and related pollination are unique. They're

famous for standing along with orchids as the only plants that

distribute their pollen not as powdery individual

grains, but all at once in special adherent packets called "pollinia." Milkweed

pollinia are arranged in pairs. The pollinia are tethered together in a

wishbone-like

paired arangement called a pollinarium that has a sticky apex

called a

"corpusculum."

Honeybee drinking nectar from Sullivant's milkweed, Killdeer Plains Wildlife Area, July 5, 2008.

A bee sipping nectar is often

forced to position her feet between hoods, and, as she pulls a leg

upwards, inadvertently hooks a corpusculum (each corpusculum has a

narrow groove

that a claw can slip into) and withdraws a polliniarium. It

remains

attached to her foot until, during a visit to a subsequent flower, if a

pollinium is positioned just right (lengthwise to the groove and

entering at a certain angle), it slips into the stigmatic

chamber, accomplishing pollination. It requires a

precise arrangement, and it seems amazing that it ever works, but

apparently it does; milkweeds set fruit abundantly.

Roses (genus Rosa

in the family Rosaceae) display many of the traits of primitive

flowers, i.e., those that most resemble a branch with leaves, because

that's basically what a flower is: a short branch with highly modified

leaves. Rose flowers have separate, not fused, petals. Also

there are numerous stamens and carpels (seed bearing units)

arranged in a spiral fashion.

Prairie rose, Killder Plains Wildlife Area, July 4, 2008, Marion County, OH.

Prairie rose, Killder Plains Wildlife Area, July 4, 2008, Marion County, OH.

Unlike buttercups

(family Ranuculaceae) which display all the traits of primitive flowers

including being hypogynous, i.e., the sepal, petals

and stamens are separately attached below the ovary, roses have one

more advanced trait in that they are perigynous.

Roses have a hypanthium, also called a "floral cup," which is a

cup-like structure formed by the fusion of the the lower portions of

the sepals, and stamens. The conspicuous portions of the sepals, petals

and stamens rise off the flower at the upper edge of the hypanthium.

Prairie rose

flower, July 5, 2008, Killdeer Plains Wildlife Area, Marion County OH.

Mouseover to see the flower:

split and split/labeled

Mouseover to see the flower:

split and split/labeled

What

is traditionally refered to as the rose fruit is an unusual structure

called the "rose hip." The hip is actually the expanded and slightly

fleshy hypanthium that envelopes the true fruits --numerous one-seeded

fruits called "achenes" that are generally thought of as being seeds.

Rose hips are noted to be a great source of vitamin C.

Yuccas

(genus Yucca, family Liliaceae) are famous for

being partners in an elegant mutualism with a moth. The moth, Tegeticula

yuccasella and related species,

is the sole pollinator of the yucca flowers. But instead of

offering the moth a food reward such as nectar (there is none) or

pollen (the moth has no use for it), the yucca plant instead provides a

nice place for the next generation of moths to begin their lives.

The moths are small, elongate, and ghostly white. They can be seen fluttering about yucca plants at night when they bloom in late June-early July. A female moth that has mated and can thus lay fertile eggs, visits a yucca flower and removes a ball of pollen, holding it in specially modified mouthparts. She flies with the pollen to another flower, ideally on another plant, where she inserts some eggs into the ovary of that new flower, and immediately thereafter pollinates the flower. This is accomplished by stuffing the pollen into a special receptive recess (the stigma) atop the pistil where she has just laid her eggs.

Yucca moths on yucca flower, along railroad tracks, Indianola Avenue, Columbus, OH July 1, 2008.

The moths are small, elongate, and ghostly white. They can be seen fluttering about yucca plants at night when they bloom in late June-early July. A female moth that has mated and can thus lay fertile eggs, visits a yucca flower and removes a ball of pollen, holding it in specially modified mouthparts. She flies with the pollen to another flower, ideally on another plant, where she inserts some eggs into the ovary of that new flower, and immediately thereafter pollinates the flower. This is accomplished by stuffing the pollen into a special receptive recess (the stigma) atop the pistil where she has just laid her eggs.

Yucca moths on yucca flower, along railroad tracks, Indianola Avenue, Columbus, OH July 1, 2008.

American

elm is an easy

tree to recognise

by its silhouette. According to William Harlow in "Trees of

the

Northeastern United States," elm resembles a wineglass, a

feather

duster, and/or a colonial lady upside-down. It's also well known for

being susceptible to two devastating diseases with very similar

effects:

Dutch elm disease (DED) and phloem necrosis, so travelers in open

country around central Ohio tend to see a lot of shattered

wineglasses, feather dusters that bit the dust and colonial

ladies

rightside-up. Here at Killdeer Plains

Wildlife Area in extreme northern Marion County an elm died

recently.

Two

weeks ago the

ultimate weed tree, tree-of-heaven, Ailanthus altissima,

was in flower. It was difficult to visualize those blooms developing

into the familiar one-seeded winged fruits (samaras). This week the

trees are much further

along, and it is now plainly evident that they will develop into

samaras.